Newcomers to this free-subscription, national-memory-advocating Substack might want to read the 442-word introductory post from Juneteenth 2023, “Why ‘The Self-Emancipator?’”

The New York Times reported in 2012 that around 2010, a Chinese government security officer threatened the writer Yu Jie: “If the order comes from above, we can dig a pit to bury you alive in half an hour, and no one on earth would know.”

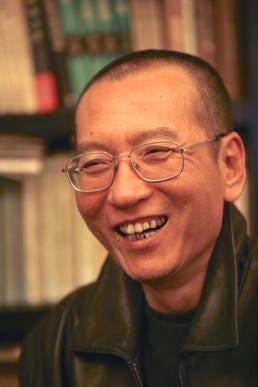

Yu was writing a biography of Liu Xiaobo, whom the Times joined many others in calling “China’s most famous political prisoner.”

Self-Emancipator subscribers and readers will recall that Liu Xiaobo’s name appears regularly here. It comes up in something like the way it did in my History News Network essay proposing a national memorial to commemorate the Civil War self-emancipation movement.

That essay nominated Point Comfort, Virginia, the site of British North American slavery’s 1619 origin. In 1861—by then containing Fort Monroe, the Union’s Virginia bastion 80 miles from the Confederacy’s capital—that same historic landscape saw the beginning of U.S. slavery’s demise.

Here’s that essay’s Liu Xiaobo excerpt:1

The proposed national emancipation memorial would address not just the country but the world. In 2020, Yale’s David Blight, the Frederick Douglass biographer, wrote that freedom “remains humanity’s most universal aspiration. How America reimagines its memorial landscape may matter to the whole world.” Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition emphasizes the “world historical actions” of the enslaved. No less than James M. McPherson sees Fort Monroe as a potential “world-class destination.” In 2021, UNESCO honored Fort Monroe’s place in world slavery history. It all calls to mind Chinese human-rights activist Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize speech assertion that “no force...can put an end to the human quest for freedom”—as seen now in Ukraine.

America’s Civil War self-emancipators vividly illustrate what Liu asserted.

In Oslo, Liu didn’t deliver the 2010 Nobel speech in person. Liv Ullman read it for him. He was in prison in China for “inciting the subversion of state power.” It was his fourth such prison spell.

Liu Xiaobo declared that “no force...can put an end to the human quest for freedom.”

When Liu was dying2 in July 2017, the Times’s Nicholas Kristof—like Liu, a veteran of Chinese tyranny’s 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre—wrote about him twice, both times emphasizing Liu as “the Mandela of our age.” In both pieces Kristof also declared that the West could learn much from Liu.

Not that it’s not common in the West to hear that “freedom is a universal human trait,” as Ken Burns put it last month in Philadelphia when the National Constitution Center honored him with its 2024 Liberty Medal. But among the reasons to quote Chinese freedom striver Liu’s declaration that “no force...can put an end to the human quest for freedom” is that doing so illustrates the sentiment’s universality and spotlights its enduring persistence against crimes against humanity.

By the way, Kristof observed in 2017 that “[m]ost Chinese have never heard of Liu Xiaobo, because the state propaganda apparatus has suppressed discussion of him.”

I can’t help linking a Self-Emancipator observation to that. No propaganda apparatus explains the puzzling lacuna of Americans’ mostly missing recognition of our Civil War self-emancipators.

But then—have I mentioned this before?—nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that Americans will eventually esteem the Civil War’s multitudes of freedom-striving, emancipation-forcing slavery escapees.

Just not yet.

Slightly edited for clarity in the present context.

Liu had a vicious cancer. Kristof wrote that the “Chinese government cruelly refused to allow [him] to go abroad for treatment” and that if “the way Liu died is an indictment of China’s repression, it also highlights the cravenness of Western leaders who were too cowed to raise his case in a meaningful manner. President Trump met Chinese President Xi Jinping in Hamburg at the G-20 summit and did not even let the name Liu Xiaobo pass his lips. For shame, all around.”

Steven- I really love the solid conclusion of this post: “nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that Americans will eventually esteem the Civil War’s multitudes of freedom-striving, emancipation-forcing slavery escapees. Just not yet.” Just not yet, indeed.