Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that Americans will esteem the Civil War's multitudes of freedom-striving, emancipation-forcing slavery escapees.

Virginia is considering restoring the original name of a place where, across a quarter of a millennium, the arc of the moral universe bent toward emancipation.1

In 1619 as Point Comfort—Jamestown’s Chesapeake Bay outpost—it saw the dawn of British North American slavery.

In1861 as Fort Monroe—the Union’s mighty, and mighty symbolic, stronghold in Confederate Virginia—it saw the dawn of U.S. slavery’s demise.

The Norfolk Virginian-Pilot and the Newport News Daily Press plan to publish an op-ed in which I’ll tell why I think restoring the name Point Comfort would be great for national civic memory and for the cause of calming the history wars.

And for more. See the caption beneath the illustration at the end below.

I’ll post the op-ed, with copyright acknowledgment. Meanwhile, this report profiles Point Comfort, especially but not only for people outside Tidewater Virginia.

(This long post has photos. Substack says that if it’s “truncated in an email, readers can click on ‘View entire message’ and view the entire post in their email app.”)

Fort Monroe—prospectively to see restoration of its 1619 name, Point Comfort—is a flat, 565-acre Gibraltar that looks across the lower Chesapeake Bay, over Hampton Roads harbor, and into four centuries of America’s past. It includes a majestic, 63-acre moated stone citadel, biggest in American history. Civil War slavery escapees called it Freedom’s Fortress.

Hundreds of ancient live oaks contribute to Point Comfort’s spirit of place.

Up close from Point Comfort's boardwalk, you can watch passing commercial vessels and warships, from container ships to submarines to destroyers to aircraft carriers (as in this half-minute video, with a passing Navy helicopter). Fort Monroe commands the entrance to the harbor containing the world's largest naval base—the harbor that saw the Civil War battle between the ironclads Monitor and Merrimac.

Lt. Robert E. Lee, with his Army engineering training, lived in this Fort Monroe house in the early 1830s as workers including enslaved Americans completed the fortress. Nearby was the cell that Jefferson Davis would occupy after the Civil War. President Lincoln, in wartime visits to the post, stayed at a house down the street. At Fort Monroe the Army briefly held Black Hawk, the Sauk leader and warrior. Edgar Allan Poe was stationed at Fort Monroe during Army service.

Limited, split national monument

When the Army announced in 2005 that Fort Monroe would retire in 2011, a Newport News Daily Press editorial declared that Fort Monroe’s future was largely for Hampton, “its businesses and its residents to control.”

Yikes. Soon I published an op-ed challenging that widespread parochial presumption about a national treasure. By spring 2006, I had published similar op-eds in both Tidewater dailies, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, and the Washington Post.

But the late Dr. H. O. Malone, a distinguished Army historian, saw that the country—the country—needed more than just regional opinion writing. We needed a better way to challenge parochialism that was founded in overdevelopment fervor and defended on perversely mistaken grounds of public financial necessity.

So five of us began organizing to advocate a sensible national park. The other three were Sam Martin of Hampton and the Norfolk preservation leaders Mark Perreault and the late Louis Guy.

A larger committee evolved, called Citizens for a Fort Monroe National Park. A crucial member was the late Gerri Hollins. She was a Black activist who spoke spell-bindingly to audiences about the freedom-striving Civil War slavery escapees discussed below.

In 1960, almost all of Fort Monroe had been designated a national historic landmark. We advocated a national park only extensive enough to preserve and cherish the historic spirit of place.

Often H. O. would shake his head and marvel ruefully at the prospect of condos—a real threat at the time—in the shadow of the majestic nineteenth century fortress. Regularly, in some two dozen op-eds over the years, I would muse about this grotesque idea: a housing development on a Monticello hillside.

But Point Comfort is prime urban waterfront. And we found out what we were up against when Hampton purported to openly invite public discussion and suggestions in long citizen sessions in the city’s huge convention center.

At the public pre-meeting assembly the night before, I stood, asked for, and got confirmation that there’d be none of the rumored prohibition of national park discussion. But in the morning, with participants ready at a multitude of round tables, an official rose to the podium and bluntly rescinded the confirmation.

Correspondingly, each table had an enforcer, though their success in forbidding national park discussion was limited. Still, it all called to mind the warning I had heard from a neighbor: “Steve, you ain’t never gonna stop ’em developers.”

That’s how it was. Skipping over the complex struggles of the next five years, I’ll report that by 2011 we had mostly, but not entirely, failed.

When the Army actually left in 2011, overdevelopment-intent Virginia politicians masterfully marginalized voices like ours. They simply contrived and politically engineered a limited, bizarrely split, Potemkin-reminiscent national monument. Please see the two green parts of the illustration below.

Most news reporting from beyond Tidewater, and often even from within Tidewater, treats the retired post in its entirety as a national park. Occasionally, for years, well-intentioned locals mistakenly congratulated us for having inspired creation of a national park. The marginalizers won.

Silly us. Sure, Captain John Smith of Jamestown, recognizing Point Comfort’s strategic importance, had first fortified it in 1609.

Yes, for almost four centuries, Fort Monroe and its predecessor forts on Point Comfort had served as the Gibraltar of the Chesapeake, with big guns to guard the lower Chesapeake Bay and Hampton Roads harbor.

True, Fort Monroe is increasingly and credibly ranked alongside the likes Plymouth Rock, Gettysburg, and the Liberty Bell. UNESCO now recognizes it as a Slave Route Site of Memory. No less than James M. McPherson, the eminent Civil War historian, writing in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, called Fort Monroe a potential “world-class destination.”

That’s all because Fort Monroe—with its Point Comfort framing—is the preeminent historic landscape for national memory of the Civil War’s hundreds of thousands of freedom-striving slavery escapees, called self-emancipators by some historians.

When Union soldiers and sailors—including 200,000 Black Americans, at least half of them formerly enslaved—began making slavery’s eradication possible, these self-emancipators forced slavery’s fate onto the American political agenda. That verb forced will surprise or even vex some readers, but it regularly appears in this context from scholars.

In May 1861, mere weeks into the Civil War, enterprising slavery escapees Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend asked for asylum at Fort Monroe, provoking momentous events that McPherson, in his Virginian-Pilot piece, called “the story of the end of slavery in America.”

On a 2015 Civil War sesquicentennial panel with Ken Burns and Yale emancipation historian David Blight, Adam Goodheart, author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening, described the momentous answer the three self-emancipators got. The fort’s commander designated them contraband of war and kept them, making the federal government their liberator—a “revolutionary change,” Goodheart declared, since always before, “U.S. authority had protected slaveholding as a constitutional right.”

If there’s really to be a reframing, a rebranding, of Fort Monroe, I think Virginians should continue to call those May 1861 Fort Monroe events what they were: the start of emancipation’s wartime political evolution.

But I also think Virginians should acknowledge that it was not the Fort Monroe commander’s reactive decision that started that political evolution. It was the three risk-taking slavery escapees’ active one.

That the three came to the very site where slavery had begun a quarter-millennium earlier is part of why restoring the name Point Comfort would matter.

Baker, Mallory, and Townsend, forerunners of those hundreds of thousands of self-emancipators across the South, recognized the freedom opportunity inherent in radically new circumstances. Self-emancipators acted with historic agency—not as “the passive bystanders of conventional wisdom,” as Burns has put it, but as active agents in an “intensely personal drama of self-liberation.”

McPherson has said that they “forced the issue of emancipation.” Civil War and slavery historian Edward L. Ayers, president emeritus of the University of Richmond and holder of the National Humanities Medal, once called Fort Monroe’s May 1861 freedom story “the greatest moment in American history.”

Not just “a” great moment in American history. “The greatest.”

All of these things are true, and clearer now than in 2011, when some still thought condos would be nice for Fort Monroe. Most never heeded Burns, though, in his The National Parks: America's Best Idea series, explaining the old, perverse pattern: powerful interests resist national parks fiercely, but in cases when they lose, they actually win. Soon they fiercely appreciate the benefits.

In the years after 2011, the Save Fort Monroe Network used this handout showing how the split national monument could be unified and expanded in the spirit of preserving and cherishing spirit of place. It could still be done. Accommodations would have to be made for sensible long-term (but not eternal) use of a number of valuable structures, but it has always been possible.

Today Virginia's Fort Monroe Authority manages Fort Monroe with the city of Hampton and—to a token extent—with the National Park Service. An official web page proclaims the vision that Virginia’s leaders have consistently intended since the Army’s 2005 retirement announcement: “to redevelop this historic property into a vibrant, mixed-use community.” The page never even mentions the national monument or the National Park Service.

A sentence from Wikipedia further illustrates Virginia’s parochial intentions for this national treasure: “Several re-use plans for Fort Monroe are under development in the Hampton community.” During the Fort Monroe politics before 2011, we condemned that as the Hampton-owns-it presumption.

Still, in 2017—thanks to constructive encouragement by the Black activist Juneteenth leader Sheri Bailey—the mayors of Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach advocated “a unified national monument.” They wanted to see it “incorporate all or most of the area” shown in red in the illustration just above.

The mayors emphasized Fort Monroe’s “special place . . . in world history,” involving both the 1619 arrival of the first captive Africans and “the 1861 beginning of slavery’s demise.” They saw Fort Monroe as “the new fourth node in the elevation of Virginia’s Historic Triangle” — Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown — “to its Historic Diamond.” I had promoted that idea—originated by others—in a 2007 Richmond Times-Dispatch op-ed.

The Daily Press buried news of the mayors’ statement in a terse blurb inside one of those hodgepodge, back-pages news summaries.

But calls to unify the split national monument also came from the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, from what was then called the Civil War Trust, from the National Parks Conservation Association and, in 2014, from Virginia’s then-Gov. Terry McAuliffe.

In 2024, nobody talks anymore about what’s in fact still possible: unifying the national monument and establishing a Freedom’s Fortress National Park. But what are the implications of the prospective new name?

Implications of the prospective new name

In the context of arguments over Confederate statues, historians have long talked about redefining America’s memorial landscape altogether, including by establishing a national emancipation memorial. My short 2022 History News Network essay advocates the natural place for that: Point Comfort.

And I called it Point Comfort, not Fort Monroe. Slavery came first. Fort Monroe, the Civil War, and emancipation came much later.

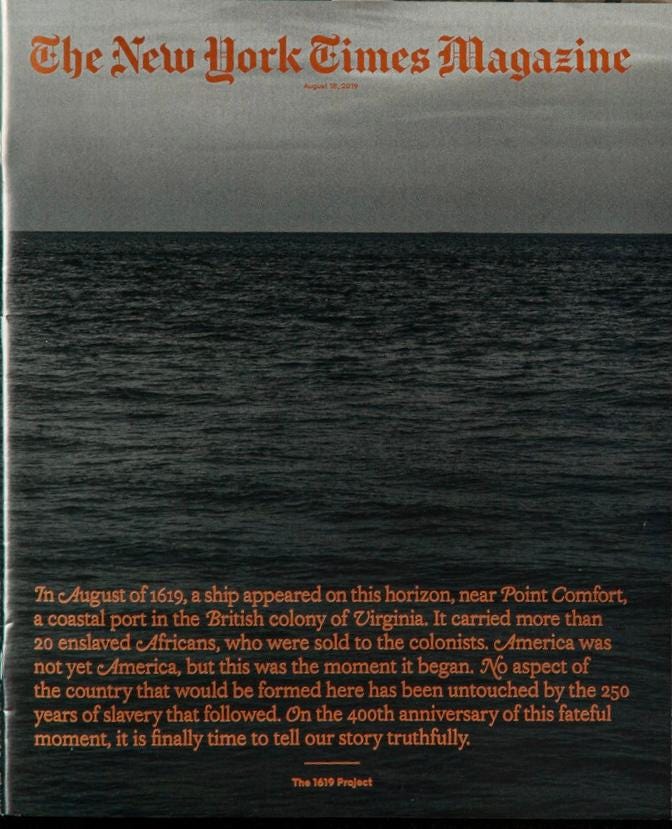

But for Virginia to start officially calling Fort Monroe Point Comfort, and to promote the place that way, would inevitably mean inviting more of the bitter, enduring history-wars skirmishes—and sometimes battles—over the 1619 Project of the New York Times.

In 2019, New York Times Magazine displayed this cover to introduce the 1619 Project, an enduring focus of history-wars contentiousness. Note the first sentence, citing Point Comfort. But note also that this view toward the Atlantic Ocean is precisely from the Point Comfort site of Virginia’s forthcoming African Landing Memorial. There’s a reason for invoking the Atlantic Ocean for these matters of Black history in America: it’s all bigger than Black history, which ultimately is American history—and it’s bigger than that too. When looking toward the Atlantic from this civic-sacred point on Point Comfort’s southern shoreline, if you turn around, you see the best possible U.S. national emancipation memorial. America built it 200 years ago, largely with enslaved labor. It got its name from freedom-striving, self-emancipating Americans: Freedom’s Fortress. The struggles of the first nation on this planet to try to found itself on principles of freedom and human dignity are not just American history. They’re world history.

That’s a big part of why I’m writing that op-ed for the twin local dailies here in Tidewater. Both strident sides in the 1619 Project battles are wrong. Stay tuned, please. And post comments. And subscribe, for free.

- - -

Yes, I hold the abolition inevitability belief. I’m glad to debate it. And yes, as with deliberately borrowing “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate” from Jefferson, I deliberately borrow “arc of the moral universe” from Rev. King.